Through a Glass Brightly

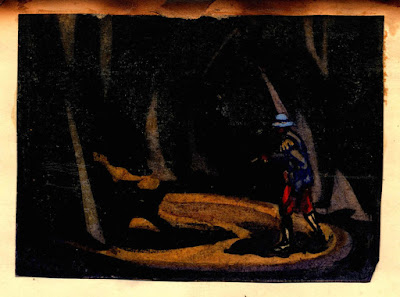

Dolly Travers-Smith's nightmarish design for Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones in 1927 was unlike anything at the Abbey Theatre before. Source: Abbey Theatre Digital Archive, NUIG.

In 1927 the Abbey Theatre’s producer Lennox Robinson spent Christmas in Cannes with his new girlfriend. Dorothy Travers-Smith - known as Dolly to most - was a portrait painter who began designing productions at the theatre that year. Cannes was a favourite destination of theirs. They visited again in 1937, but by then their lives had changed forever.

Dolly had an unconventional upbringing in the otherwise upper-class area of Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin. Her mother Hester was believed to have psychic powers. She divorced her husband, a well-regarded physician, before setting up shop as a medium. In 1915, Lennox participated in one of Hester’s séances. He was probably already friends with Dolly when she arrived at the Abbey in January 1927. By November, Augusta Gregory recorded in her diary that ‘a young lady‘ had ‘fallen in love with L.R’.

Norah McGuinness was still designing at the Abbey when Dolly started. Together, their abstract designs lent a sudden and intense contemporaneity to the theatre’s displays. They also became life-long friends.

Where Norah tended to focus the backcloth as if it were a modernist painting, Dolly showed her wealth of references for architectural and sartorial detail. She manipulated old machinery to stirring effect for Eugene O’Neill’s expressionist drama The Emperor Jones. Her ancient Egypt-style costuming for Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra was cut to shorter lengths than usual garments onstage. Vivid landscapes backings were painted for revivals of Shaw’s John Bull’s Other Island and Gregory’s Spreading the News. The only design she seems to have been paid for was the haunted farmhouse set for John Guinan’s Black Oliver - £3-3-0, the equivalent of €209 today.

When they arrived in Cannes, Dolly and Lennox - who directed an exhausting number of productions as producer - must have needed a break. The city was undergoing a subtle reconstruction. The new decorative style Art Deco, christened two years previous at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, was beginning to shape the landscape. Building had begun on the iconic Hôtel Martinez, and attractively geometric embellishments popped up along the city’s promenade, la Croisette.

Last year I went on holiday to Cannes. I saw those wrought iron marvels up close and felt myself slipping back in time to the ‘roaring Twenties’.

Art Deco facade on la Croisette, 2017.

Dolly was clearly a contemporary designer. She redeployed classical forms with fresh energy in Caesar and Cleopatra. She met the demands of expressionism, the major avant-garde style, in The Emperor Jones. I can’t imagine her oblivious to the Art Deco inventions taking place around her in Cannes. In fact, I’m beginning to think the visit inspired her radical design for King Lear.

In 1928 the Abbey Theatre found itself at something of a crossroad. It had long committed to plays by Irish playwrights, often set in farmhouse kitchens. But some productions by the Dublin Drama League - the theatre’s subscribers-only club experimenting in non-Irish plays - were brought back and billed as Abbey Theatre productions. The theatre seemed on the verge of embracing international writers like Eugene O’Neill, Susan Glaspell, Henrik Ibsen, Gregorio Martinez Sierra and the Quintero brothers as part of its repertoire.

A bold step was taken: Denis Johnston, a young lawyer with great knowledge of theatre beyond Ireland, was hired to direct King Lear, the Abbey’s first production of a Shakespeare play. Dolly was even paid to design it - £10-10-0 (equivalent of €702) for the designs and £4 (€281) a week for scenic painting. It was the biggest investment on design for an Abbey production yet.

These designs, painted in vibrant watercolours, show a simple plan to accommodate the tragedy’s many scenes. Clear backings - decorative walls for the castle interiors, for instance, or a lightning bolt for the storm scene - could be rolled out to transport the production between settings. These had a fascinatingly modern character. The stained glass window for Lear’s throne room looks Art Deco in its mix of classicism and abstraction. In fact, audiences would have seen the decorative style as simulated here before Dublin Art Deco buildings such as the Gas Showrooms on D'Olier Street and Noblett's Corner on Grafton Street were built by the architecture firm Robinson + Keefe in 1932.

Dolly's set design for Lear's throne room, 1928.

Furthermore, there’s a futurist element to the window’s spectacular and violent clash of traditional emblems - a bronze lion, flags in blue and white, yellow and black - that streak out in different directions, much like the dividing of Lear's kingdom. From this offsetting of colour and abstraction of familiar icons, we could speculate that Dolly saw Mainie Jellet’s futurist painting A Decoration, itself an abstract take on the Madonna picture, when exhibited in 1923. We can also imagine that audiences didn’t just witness the traditional playing of King Lear being repudiated. On such a night, the Abbey Theatre and its stage displays must have felt full of possibilities.

Unfortunately, this energy wasn’t taken advantage of. Though actor F.J. McCormack received wide praise for playing Lear, the production didn’t seal a critical or commercial success that would broaden the Abbey’s programming into international work. 'Lear was put on to show what Denis Johnston can do,' wrote Augusta Gregory, ‘& has but shown what he can’t'.

Yet there had been an audience for plays and design from further afield, and the new Gate Theatre soon took full advantage. Competing against the immensely detailed sets and costuming of Micheál Mac Liammóir and the sculptural lighting of Hilton Edwards, Dolly and Lennox suddenly had a fight on their hands, one that W.B. Yeats felt they could win. When Dolly asked him for feedback in 1929, Yeats replied: ‘You have transformed the look of our stage’.

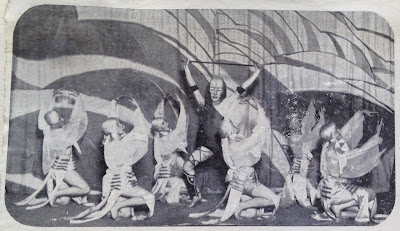

According to novelist Frank O’Connor, a board member of the Abbey, Yeats would get furious at any mention of the Gate, saying: ‘Anything Edwards and Mac Liammóir can do, Lennox and Dolly can do better’. Sure, they dealt a Ballets Russes-inspired blast of orientalism to Yeats’s dance play Fighting the Waves, and found expressionist use of puppets for Lennox’s Ever the Twain. But Irish kitchens and parlours soon reasserted their dominance, and Dolly’s engagement with the theatre never became full-time.

Dolly's set and costuming for Fighting the Waves by W.B. Yeats, 1929.

On January 6th 1931 Dolly and Lennox were married. The Abbey company's U.S. tour was chosen as their honeymoon. In one city, Dolly got the attention of a journalist who observed ‘the little woman (not five feet two) in the lipstick red evening frock, who stood around in the lobby while her tall husband smiled at her from behind a barrage … mostly women’. Lennox seemed to deal better with attention than her (‘I don’t know why you want to write a story about me,’ she told the journalist). He was also starting to drink more.

In 1932 Dolly finally got a set wage - a first for any designer in the Abbey - £5 (€389) per set and £2 (€156) per costume. This is a noted decrease on her remuneration for King Lear. Also that year, Augusta Gregory died and Lennox was entrusted with greater responsibility for running the theatre. His drinking, and likely burnout, led to a systemic problem reflected in the bad standard of Abbey productions, and, most surely, in his relationship with Dolly.

The American journalist described Dolly as ‘intensely interested in all phases of modern drama’. But her career as a designer had become tethered to Lennox’s bad management. In 1934 a new producer and a new full-time designer for the Abbey were hired. Lennox was soon shown the door. Dolly, who doesn’t seem to have been considered for the designer job, went with him. One of their last collaborations at the Abbey was the European premiere of Eugene O'Neill's expressionist play Days Without End, probably to recapture the success of The Emperor Jones. The production featured more stained glass windows.

It must have been an immensely struggling time for Dolly, seeing both her stage design career and Lennox fall apart. She seems to have found an escape through landscape painting, and held exhibitions in the 1930s and 40s. Reviews suggest intense red palettes and ethereal Mediterranean scenes. ‘Mrs. Robinson has a secure place among conventional landscapists,’ wrote a critic, but I haven’t been able to find any of her paintings.

Dolly worked as curator of the Joyce Museum in Sandcove before her death in 1977. Lennox died 18 years previous, and they didn’t have children. I wonder if Norah McGuinness sensed an erasure of her friend’s work when she spoke to the obituary writer: ‘She had been a close friend of W.B. Yeats’.

When Dolly and Lennox returned to Cannes in 1937, their careers in the Abbey Theatre were over but she would have begun work on her first art exhibition, held in St Stephen's Green the following year. I like to think that at the moment she smiled for a photo outside their Cannes villa, the disappointing end of her stage design was already behind her. As a modern artist, the future was what mattered.

Dolly Travers-Smith in Cannes, 1937.

Comments

Post a Comment