A Night at the Ancient Concert Rooms

Where might a design history of the Abbey Theatre begin? The Academy on Dublin's Pearse Street, site of the old Ancient Concert Rooms, is a good place to start.

You’ll find more disturbing accounts of researchers and how their lives are held ransom by ghostly documents. Last week I caught a break. I finally got my hands on Catherine Morris’s excellent Alice Milligan and the Irish Cultural Revival. I shook off my ignorance and satisfied some suspicions. As an all-round theatre impresario - playwright, producer, designer - Alice’s influence on Irish stage design has been more prodigious than I realised.

Alice's theatre-making was as freshly energetic as her appearance (there's a photograph of her at 30 in which she looks about 20). Born near Omagh in 1866, Alice was of age to take part in the Celtic Revival. There are many explanations for how this period of cultural regeneration came into being. Most view it as a reaction to the death of Charles Stewart Parnell in 1891, an anarchic politician who got Irish issues on the agenda in Westminster. If there was a spark, it grew into a blaze in time for the centenary of the United Irishmen Rebellion, commemorated in 1898.

On a visual plane, however, the mobilisation of designers to recall Ireland’s heroic past (the Arts and Crafts Movement) may have had less to do with politics and more to do with regenerating scenes around the country. Ireland was suffering the fallout of the Famine and the consequent overcrowding in slums. It’s worth remembering that by the time the Gaelic League got itself established in 1893 to promote the Irish language, the Irish Industries Association was already organised and showcasing Irish design at the Chicago World Fair, an envoy that Alice was a part of. But I won’t go into that here.

Alice Milligan, enduringly youthful.

The event I’m curious about is a production at the Ancient Concert Rooms on Brunswick St (now Pearse St) in April 1901. The idea came from Maud Gonne, founder of the women’s nationalist organisation Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland). She had seen Alice’s work in Belfast the previous year. “You have such a genius for dramatic effects,” she wrote in a letter. “If you came we are certain of a magnificent success”. She wanted Alice to produce a play in Dublin for the Inghinidhe.

What Maud had seen in Belfast was one of Alice’s tableaux plays. Hard to believe now but tableaux vivants (living pictures) were a well-known form of performance at the time. These were theatricalised episodes from history, art, or simply real life, played out through choreographed scenes. Performers strike a pose, stand still for a few moments, then move into a new gesture.

Alice’s tableaux took inspiration from heroic sagas of Irish mythology, and made legendary figures like Queen Maeve and Grania flesh. Her colourful costume designs show reimagined forms of Celtic dress: tunics and robes with spiral and zoomorphic embellishments, dressed with penannular brooches. As far as I can tell, Alice’s production for the Inghinidhe was the first time these Arts and Crafts-style designs were seen on a Dublin stage.

To give a sense of this production's scale: throughout the night, more than one hundred people are ushered on and offstage (a busy evening for the stage manager W.G. Fay). For the Battle of Clontarf, two armies armed with papier-mâché helmets and shields freeze in their warrior poses. It's the cue for a hidden choir to start the old song Return from Fingal. Seconds later the armies recede, allowing Brian Boru to come into view, frozen as he's struck a killing blow by an enemy’s sword. The choir’s song lilts into mournful strains of the Irish caoine, or lament (often associated onstage with J.M. Synge’s play from 1904, Riders to the Sea, but seen first in Alice’s tableaux).

On this night, a single page from the annals of Irish myth and history doesn’t go unturned. Audiences see the pirate queen Grania Mhaol confronting Queen Elizabeth. Sarah Curran and Anne Devlin assist Robert Emmet. The Children of Lir take flight. Performers come and go, dressed in poplin and wool, their wigs in cavaliers and plaits. Queen Maeve’s legendary chariot, a sure centrepiece, has been fashioned from armchairs.

Alice's costume designs for reimagined Celtic dress. Spotted in Catherine Morris's excellent Alice Milligan and the Irish Cultural Revival.

Interestingly, a highlight for the Dublin press wasn’t a myth-inspired episode but rather a quaint slice of realism. One tableau takes a cottage as its setting, and depicts life in rural Ireland. A woman is seen rocking a cradle while a man lights his pipe. Both break character when they spot someone in the audience.

Douglas Hyde, president of the Gaelic League is pulled onstage and the tableau breaks into a dance. This seems to have been charmingly novel for Dublin audiences. “The introduction for the first time in the metropolis of a cottage ceilidh scene representing the actual everyday life,” wrote the United Irishman.

If I had to guess, Alice’s production took its tone from the illustrations of nationalist newspapers like the United Irishman and the Weekly Freeman. These often depicted Ireland as woman (Erin), gagged and chained, struggling against a colonial oppressor. It wasn’t a big surprise, perhaps, that she staged the well-known image: ‘Erin Fettered, Erin Free’. One tableau shows Erin at the base of a Celtic cross, crouching miserably over her unstring harp. In the next tableau she’s upright, the red cap of the French Revolution on her head, a sword in her hand.

According to the United Irishman, it was such a stirring sight, the audience shouted ‘Aris! Aris!’ (Again! Again!), and the actors repeated the sequence several times to applause. This seems to have been a more roaring response than the lively ovation for Cathleen ní Houlihan - Augusta Gregory and W.B. Yeats’ explicitly nationalist play - which would premiere a year later.

Yeats imagined a theatre for Ireland staffed with English actors. But in August 1901, he saw Alice’s plays for Inghinidhe na hÉireann, The Deliverance of Red Hugh and The Harp That Once, and claimed: “I came away with my head on fire”. From then on he was obsessed with hearing his plays spoken in an Irish accent, and the road to founding the Abbey Theatre came into view.

A year later, in April 1902, Inghinidhe na hÉireann produced the premiere of Cathleen ní Houlihan. Due to the fault of either Yeats or the critic from the Freeman’s Journal, the contribution of the Inghinidhe players was completely forgotten during the curtain call speech (*). As the campaign for an Irish national theatre kicked into gear, the public focus remained firmly on literati such as Yeats and Gregory, and the brothers W.G. and Frank Fay (who I'll share more about in the next post). Combined, they would build on the hard work done by Alice Milligan. In return, none of them produced her plays at the Abbey.

The inroads Alice made in terms of stage design, however, especially the rigour with she reimagined Celtic costuming, would receive several variations by other designers in the years to come.

Some of the Inghinidhe players didn’t forget the potency of those first designs by Alice. When they were imprisoned in Kilmainham Jail during the Civil War, they made an extraordinary decision. With their inmates as an audience, they transformed again into Anne Devlin and Robert Emmet, and replayed their tableau from twenty-two years previous. If Alice gave Irish theatre anything, it was a window onto what an Irish revolution could look like.

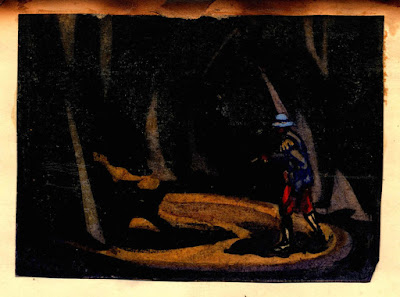

Alice's costuming for Queen Maeve.

(*) Mary Trotter is to thank for noticing this, in her book Ireland's National Theaters.

Comments

Post a Comment