Modern Art in the 1920s

Occasionally in the 1920s, the Abbey Theatre was a place where you could go see modern art.

The next time you pass these windows, you should spare a thought for Norah McGuinness, a widely uncelebrated modernist painter who, for three decades, created arresting displays for these windows. She’s also the next designer to enter this story about the Abbey Theatre, working there for 20 months between 1926-1927.

The Twenties are remembered for their prosperity more than any other decade. In France, the U.K. and the U.S, the attractively new geometric forms of cubist, expressionist and futurist art were embraced in the ritzy style of Art Deco, signalling freedom, wealth and exuberance after the Great War. But Ireland lay shattered in the 1920s after the War of Independence and Civil War, with a new Free State government struggling to pick up the pieces.

That’s probably a more likely landscape for modernist art that could reject history as recognised. In 1923, the radical cubist Mainie Jellet had her first exhibited paintings described by the Irish Times as ‘two freak pictures’. Others continued where avant-gardists from the Arts and Crafts movement such as Harry Clarke and Wilhelmina Geddes left off - presenting Irish subjects in recognisably international forms. It was Norah’s geometric control that appealed to W.B. Yeats, who first met her through her poet husband Geoffrey Phibbs. She did Byzantine-style illustrations for Yeats’s stories about an Irish poet, Red Hanrahan. In 1926 he asked her to design set and costuming for the Abbey’s revival of his play Deirdre.

Norah's costume design for Deirdre combines Arts and Crafts elements like pelta embellishment with modern geometric detail. Source: V&A Collections.

As we’ve seen before, the Abbey company was interested in using modern art in its displays as far back as George’s Russell’s Arts and Crafts-style costuming for his own Deirdre play in 1902. This never evolved into a full commitment; in the last post, I showed that a realist exactitude to Irish domestic life became the company’s preoccupation. But on the rarest of occasions, the Abbey was a place where you could see contemporary stage design from England. The Hour Glass was staged with the latest moveable machinery in 1911, and Cuchulainn was put in oriental-style dress for a 1919 revival of On Baile’s Strand. Yes, there were both Yeats’s plays - he probably paid these commissions out of his own pocket - and no, these resources barely extended to other playwrights’ works. Norah was the latest modernist to give his work a facelift.

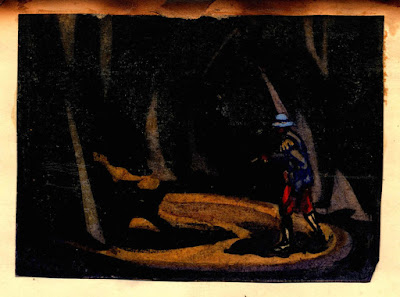

Much like Robert Gregory before her, Norah seems to have had a painterly approach to stage design. Perhaps exaggerated brushstrokes to a stage backcloth could, like a piece of expressionist art, create a scene full of anxieties and yearnings. The Irish Times critic wasn’t a fan: ‘The dresses [in Deirdre] were beautiful and the stage draperies nice to look at, but the planning of the backcloth would not convey even to the mind steeped in symbolism the idea of a forest in a grey-blue light’. It was the first time Norah gave a critics a run for their money.

A month before Deirdre, the Abbey was stormed by riots during the premiere of Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars. A few months later, it was possibly attracting controversy again, this time with the first Irish production of The Importance of Being Earnest since Oscar Wilde’s trial for gross indecency. Director Lennox Robinson wrote in a programme note: ‘The time seems to have come when the ‘Importance of Being Earnest’ needs to be definitely dated’. The play was barely 31 years old.

Lennox’s note was something of a contradiction. Yes, Earnest began in shingled hair and plus fours, a decidedly period production that could safely distance itself from its controversial author. But for the second act, when the comedy moves from a city flat to a country garden, an intense-sounding modernist backcloth was released to set the scene. Norah designed this, and it’s one of the frustrating gaps in my research that there isn’t a photograph of it. If you look closely at the centre of the photograph for act one, you can see some of its abstract detail. Funnily, Norah’s design was a more contentious aspect of the production than Wilde’s trial. One critic complemented her ‘quiet and artistic garden’. Another groaned it ‘left the impression of forlorn and irrelevant figures battling feebly against a sea of paint’.

Act I of The Importance of Being Earnest (1926) is set in a city flat. The two folds of fabric in the centre show detail suggesting it's Norah's backcloth. Source: Abbey Theatre Digital Archive.

The Importance of Being Earnest was the most popular production designed by Norah, returning again in 1927. Around this time, she also designed golden costumes and masks for Yeats’s new dance play The Only Jealousy of Emer, staged for one night only by the Abbey’s subscribers’ club, the Dublin Drama League. She probably made the tapestry-style cloth for Sancho’s Master, Augusta Gregory’s adaptation of Don Quixote. Significantly, she designed the production of Georg Kaiser’s expressionist play From Morn to Midnight that opened the brand new Peacock stage, using the stepped visuals seen in experimental German films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu.

Of all the designers I have met on this journey, Norah has been the most vocal about its frustratrions. ‘It’s an appalling, thankless job and directors can never make up their minds,’ she said. I’ve no doubt she argued her corner. Once, she arrived at a hellish situation in the Yeats household of having to discuss W.B.’s obscure new book A Vision. One party guest, the critic Sean O’Faolain, later admitted they were all terrified of her.

Norah left stage design and worked as a painter in Paris and London before returning to Dublin in the 1940s. It was during that isolationist decade she managed to co-found the Irish Exhibition of Living Art to celebrate international art, a kind of precursor to the Rosc Festival. By the time she had garnered enough reputation for an exhibition in her home city of Derry, the Lord Mayor’s wife refused her an invitation because she was a divorcee. But her work spoke for itself; in 1950, she represented Ireland in the Venice Bienalle. One of her paintings, The Startled Bird (1961), hangs in the National Gallery, near Mainie Jellet’s A Composition.

Norah's explicitly expressionist set design for From Morn to Midnight (1927).

Amidst all this later success, Norah would actually return one last time to design at the Abbey. But that would be getting ahead of ourselves.

Norah McGuinness in 1969.

Comments

Post a Comment