Who was the Abbey Theatre's First Stage Designer?

Until the mid-20th century, stage design was rarely seen as more than scene painting and two-dimensional pictures.

Josef Svoboda, the Czech designer who revolutionised lighting in theatre, once admitted: “My great fear is that of becoming a mere ‘décorateur’.” Nowadays designers can expect to be credited directly below directors in programmes but it’s a relatively recent trend. Up until the mid-20th century the discipline was widely thought of as nothing more than scene painting and two-dimensional pictures.

The Abbey Theatre’s board displayed this attitude by delaying as long as it did before hiring a resident designer. (Place your bets in the comments section on just how long). That’s not to say we won’t see some interesting commissions along the way.

Design is inevitably part of any production. If the company of players that founded the Abbey desired to produce plays with Arts and Crafts-style displays like those Alice Milligan exhibited (spiral and zoomorphic embellishments, medieval dresses, penannular brooches, etc), they’d need someone up to the task. The company's designer W.G. Fay, industrious as he was, didn’t feel qualified.

Recalling George Russell’s myth play Deirdre, which shared the billing with Cathleen Ní Houlihan in April 1902, Fay wrote: “It was far out of my line. I saw Russell and left the designs entirely in his hands”. Russell’s designs were less concerned with the drama’s settings - the interior of a fort, a bank by a loch, the inside of a regal house - and prioritised Celtic costuming with fine knotwork interlace. Russell, like Alice, was someone likely to be hands-on in the founding of the Abbey but wasn't.

In 1903, when it came to staging a serious follow-up to Cathleen Ní Houlihan, it was probably Augusta Gregory who recommended her son Robert (pictured above) for designing set and costuming. A 22-year-old flunking Oxford student but star cricketer, Robert had recently expressed desire to be a painter. Before starting at the Slade School of Art in London, he contributed a coloured sketch for Yeats’s The Hour Glass.

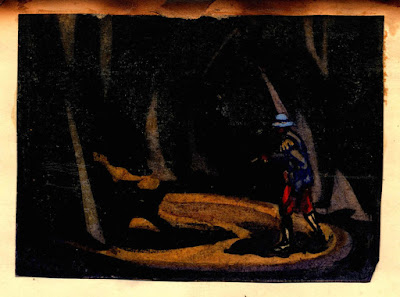

Robert Gregory and Thomas Sturge Moore's set and costuming for The Hour Glass by W.B. Yeats.

Yeats’s morality play shares a lot with Goethe’s Faust, including a medieval scholar’s study breached by biblical beings. Robert’s design, while showing a painter’s eye for composition, didn’t include measurements or details for how to build the set for the stage of the Molesworth Hall. Yeats reached out to Thomas Sturge Moore, the designer who made dust jackets for his books, who supplied a more detailed drawing. (*)

The result was an olive green hessian curtain for the walls of the study, with characters coming and going in shades of purple and brown. Yeats was so satisfied with it, he even gave a post-show lecture on harmonising colour in stage design: “It should be thought out not as one thinks out a landscape, but as it were the background of a portrait”. Joseph Halloway, the Dublin theatre diarist, observed that the audience didn’t find the talk riveting

If Yeats believed that single notes of colour worked best for ancient Irish plays, he must have twitched when Annie Horniman, the English producer who became the company’s patron after seeing The Hour Glass, started sewing beads and tracing patterns onto garments. Horniman’s costuming for Yeats’s The King’s Threshold, showing a poet’s hunger strike after his dismissal from court, has received negative criticism from Yeats scholars. Richard Allen Cave called it “amateur in the worst senses of the word”.

It was more likely in the wrong place at the wrong time. Annie’s costuming for court women and knights in The King’s Threshold, featuring geometric bands and medieval silhouettes, owes more to the principles of Carl Emil Doepler’s savage dress for Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle than the soft blues and greens of reimagined Celtic dress as emerging out of the new Dun Emer studio (whose directors included Elizabeth Yeats and Lily Yeats, W.B.’s sisters). Annie’s Germanic figures must have looked out of place in the Irish design culture of the time. That effect may have been deliberate; as purse-holder, she felt that the Abbey company shouldn’t peddle in nationalist politics. As costumer, she was well-placed to prevent it from happening.

Annie Horniman's costuming The King's Threshold by W.B. Yeats.

While live performance has its unpredictable tension, Annie obviously felt that the new national theatre, which she purchased on Abbey Street in 1904, could be furnished with Irish character and still remain non-political. Before the modernist version that sits there now, the old Abbey Theatre façade had five windows from the stained glass studio Túr Gloine (Tower of Glass), embroideries on interior walls from Dun Emer, large copper-framed mirrors from metalworks at Youghal (one still hangs in the foyer today) and, most significant, the woodcut by Elinor Monsell that gave the theatre its lasting emblem: Queen Maeve, holding a wolfhound in leash. When doors first opened on Dec 27 1904, you could leaf through the programme and see Annie credited for costuming Yeats’s On Baile’s Strand. She had already left Dublin by then, after Yeats insulted her costuming in front of the company. She committed to covering 50% of all stage design expenses before she went

The Abbey Theatre directorate were aware after the theatre had opened that its company only had one-act plays in repertory. Bigger plays seemed to demand more scenery. J.M. Synge’s The Well of the Saints, premiered in February 1905, had two roadside backcloths painted by Pamela Coleman Smith, the illustrator who later made tarot cards for the Golden Dawn. Robert Gregory became a regular designer for plays with ancient settings, designing an impressionistic-sounding wood for Augusta Gregory’s Brian Boru tragedy Kincora (1905) and an intensely Arts and Crafts-style cabin for Yeats’s Deirdre (1905). He also made a harp for Yeats’s The Shadowy Waters (1906), stonewalled village streets for Gregory’s The Image (1909), and shimmering costumes for J.M. Synge’s Deirdre of the Sorrows (1910). His last commission was a backcloth for Douglas Hyde’s A Nativity Play (1911), in a translation by Augusta, painted in a similar soft pastoral tone to the oil paintings he exhibited in Chelsea in 1914.

In 1915, Robert joined an Irish regiment of the British army in World War I, eventually graduating to the air arm. An Italian pilot mistakenly shot him down in 1918. Yeats wrote four poems about the tragedy, including Reprisals, which Augusta despised in her journal: “I cannot bear the dragging of R. from his grave to make what I think a not very sincere poem”.

Hopefully these few words on Robert's ignored stage design has done something to speak the truth.

Robert Gregory's costuming for Deirdre of the Sorrows by J.M. Synge.

(*) Richard Allen Cave gives a detailed description of the design for The Hour Glass in 'On the siting of doors and windows: aesthetics, ideology and Irish stage design', The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-century Irish Drama (2004).

Comments

Post a Comment