Flagstone Floors and Open Fires

How did two brothers from Rathmines get into the business of producing plays set in country cottages?

When we first met William, he was stage manager for Inghinidhe na hÉireann’s production of Alice Milligan’s tableaux play at the Ancient Concert Rooms. He then went on to become the Abbey Theatre’s first production manager, and was responsible for designing productions - or at least those inside his frame of reference.

The Fays grew up on Ormond Road, Rathmines in the 1870s and 80s. Their father was a civil servant who expected the same of his sons. I wonder if he spotted Frank’s wardrobe steadily filling with plays by Beaumont and Fletcher, Ben Johnson and Christopher Marlowe? After school, Frank got a secretary job at the largest accountancy firm in Dublin, and William left to work technical crew with touring fit-up theatres.

On one of William's returns to Dublin, Frank, who had begun studying vocal lessons in Italian opera, asked him to stay and grow their amateur company, the Ormond Dramatic Society, into something more serious. William settled and got a technician job as part of Dublin Corporation’s changeover of the city to electric power.

Two developments shaped the Fays’ destinies during the 1890s. One was the inspiration they found in André Antoine, a one-time employee of the Paris Gas Works, who had recently established his amateur company as a significant force in French theatre. Word of the Théâtre Libre and its painstakingly realist productions spread throughout Europe. Two years ago, I found its former site in Paris. I thought of Frank and William, who never made the trip.

Théâtre Libre in Paris, 2015.

The Fays seemed as curious about the Théâtre Libre’s journey as they were about the exactitude of French realism to show a fully atomised underside of life. Remember: the bells and whistles of Dion Boucicault’s melodramas, and other writers’ imitations of such, were the golden rule of the day.

The second development was the uncovered extent to which the Irish culture industry was run by English investors. In September 1900, journalist D.P. Moran wrote an exclusive in the Leader newspaper finding the three licensed Dublin theatres - the Gaiety, the Queens and Theatre Royal - paying out £200 a night to bring in performance companies from England.

Around the same time, Frank started working as freelance theatre critic for the United Irishman newspaper where he regularly picked apart those productions’ portrayals of Ireland. The arguments for a native theatre became easier and easier to make.

Frank’s theatre criticism helped me to understand one of the domineering scenes at the Abbey Theatre: the cottage kitchen. This structure often seemed numbingly boring to me. I was sooner drawn to more experimental cases of stage design - which we’ll get to in the next blog post. But near the end of my PhD, I’ve had to address the cottage’s place in the Abbey’s design history.

I was rereading Frank’s review of The Irishman, a melodrama by the manager of the Queen’s Theatre, J.W. Whitbread. This had been one of the most popular productions to come out of that playhouse in nearly a decade but as a melodrama about the Land War, Frank took exception. ‘A crude piece of unconvincing conventionalism,’ he wrote.

The Irishman seemed to have enough patriotic lines to win the audience’s approval. But Frank wouldn’t let go of its ‘sensation scene,’ a concentrated scene in all melodramas. This one saw bailiffs arrive outside the cottage of a tenant unable to pay their rent, and using a battering ram to knock down the door. Frank wasn’t convinced: ‘It does not convey the maddening and heartrending scenes’.

Whitbread and other English actor-managers in Dublin were skilled in producing melodramas hovering closer to pathos than reality, but Frank could always bring them down to ground. The battering ram had gained a reputation as a cruel weapon destroying people’s cottage homes during the Land War. I realised that the Abbey Theatre, through its stage design, had purpose in building the cottage back up.

When I read a letter Frank sent to W.B. Yeats in the West, asking him for ‘a few examples of the interiors of cottages,’ I wondered if the Fays had ever stepped into a country cottage. A Google search of ‘Ormond Road’ returns a street covered in Victorian redbrick houses. It’s possible they had never seen in detail those buildings' whitewash walls, flagstone floors and open fires.

Conroy's kitchen, 2016.

I suddenly realised that I had! Long before I was born, my father bought a site on the edge of his farm. There sits a cottage with exposed stone walls and a ceiling of rust-red galvanised iron that once supported a thatched roof. We call it Conroy’s, after its previous owner. Several childhood adventures began with pushing open that heavy wooden door, walking through the dusty rooms and peeking outside through their low windows. It’s now a helpful portal to the past.

So, did the Abbey company get their cottage displays right? Inghinidhe na hÉireann already had some of the vital furniture - a dresser, both practical and ornamental, appears in a photograph of Augusta Gregory’s first play, Twenty Five. Gregory, living between Galway and Dublin, was tasked to source red petticoats, Aran caps and a spinning wheel for J.M. Synge’s Riders to the Sea. This resembles the Théâtre Libre’s methods for authenticity. The company once gathered costumes and objects from Paris’s Russian community for its production of The Power of Darkness.

But William and his crew - the carpenter Seaghan Barlow and electrician Udolphus Wright - couldn’t fully translate the Théâtre Libre’s innovations into displays on the Abbey stage. The set for Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World in 1907, one of William’s last productions to design, disappointingly resembles his cottage interior for Cathleen Ní Houlihan back in 1902. That set’s painted backdrop - a countryside scene peering through the cottage door and windows - was depressingly artificial under bright lights.

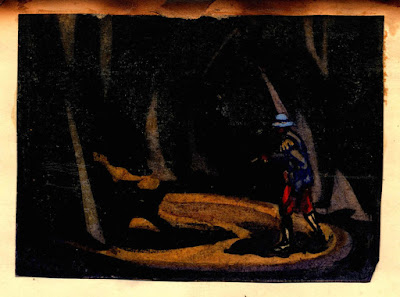

The Playboy of the Western World, 1907.

The shebeen set for The Playboy of the Western World, darker in colour and mood, is as flat. There’s probably an unfortunate irony to be found in William, an electrician involved in Dublin’s changeover to electricity, not noticing the higher-powered electric lighting and how it renders two-dimensional sets as artificial-looking. This was partly down to the footlights, which Antoine got rid of. The Abbey held onto theirs until the 1940s.

In 1908, William had grown frustrated with some actors’ lack of professionalism, and sought clear terms of authority as producer from the rest of the Abbey directors. When they refused to back him up, he resigned. Frank left too, in solidarity. William indicates in his memoir that he had become tired of the Abbey’s plays about likeable ‘peasants’.

Little did he know that change was just around the corner, in plays by Lennox Robinson, T.C. Murray, R.J. Ray, Susanne R. Day and Geraldine Cummins that dealt with provincial corruption. Realism at the Abbey was just beginning.

Lennox Robinson was made producer in 1910, and the theatre’s scenery seems to have improved under his management. Design drawings and property lists show a more detailed engagement with interiors that could blend two-dimensional painted surface alongside three-dimensional carpentered scenery to more convincing effect.

The most significant development was the rejection of painted representations of wooden beams and stones, and instead the use of actual materials, such as plaster and wallpaper, for kitchen walls.

Ann Kavanagh, 1922.

One of the earliest photographs showing this transformation is of Dorothy Macardle’s play Ann Kavanagh in 1922. Painted and carpentered forms blend more successfully here. Macardle’s play, an up-close look at violence during the 1798 Rebellion, was timely staged between the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War. This isn’t the bright-walled cottage of previous displays, a monastic piece of architecture recalling past glories. This cottage interior, stark and gloomy, now represents Ireland’s impoverished history.

Seeing the cottage in disrepair may still stir today. In the summer of 2016, I discovered that someone had set fire to the roof of Conroy’s. Scaffolding tore in strips and fell through the building, blocking any entry. It’s sad really. I’ll never step back in time again.

Comments

Post a Comment